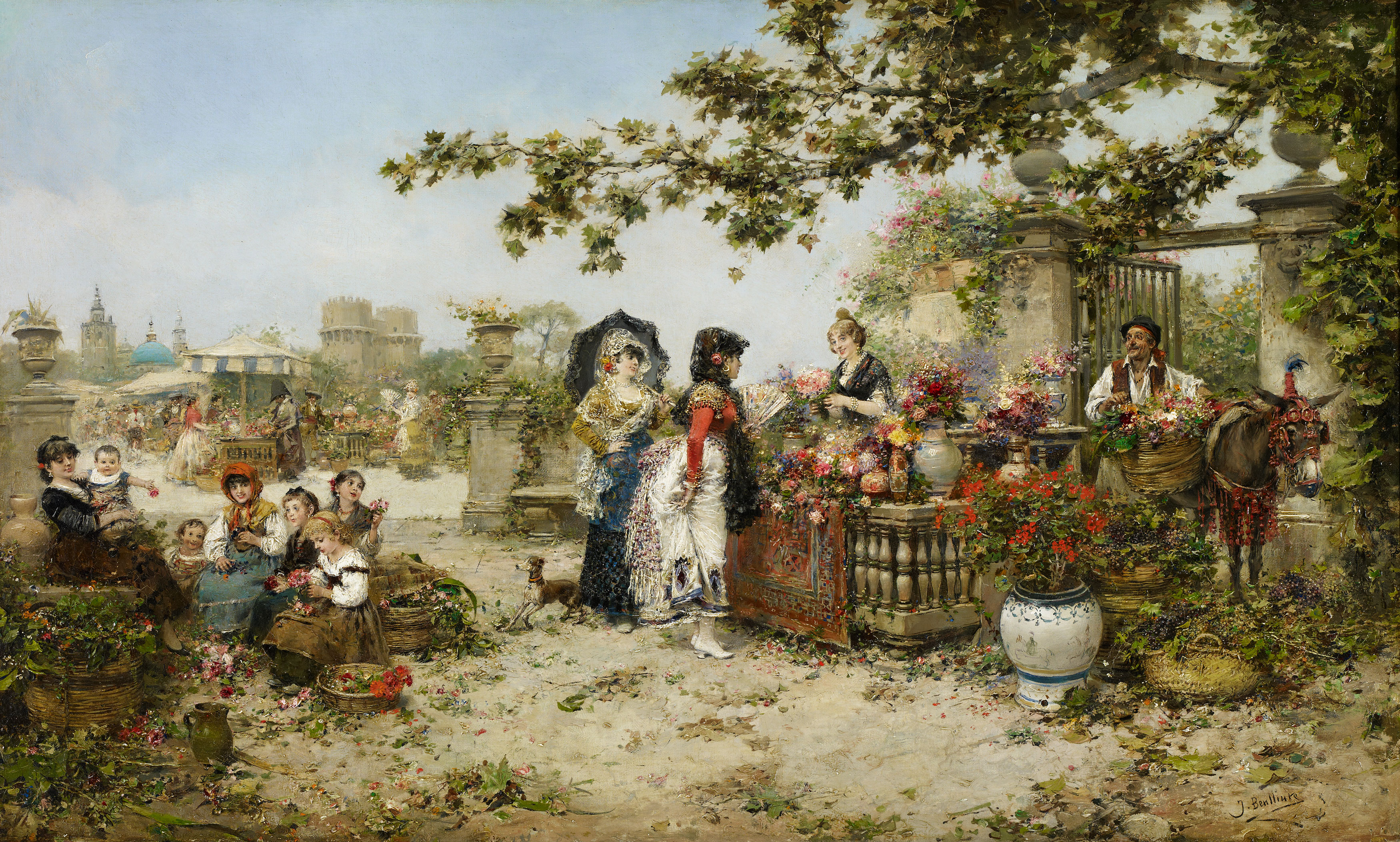

José Benlliure Gil

The Flower Market

s.f.-

Oil on canvas

64.3 x 104.3 cm

CTB.1995.23

-

© Colección Carmen Thyssen-Bornemisza en préstamo gratuito al Museo Carmen Thyssen Málaga

The Flower Market can be classified with a number of other pictures in José Benlliure’s production which date from his Rome period (1879–95). In the 1880s Benlliure's style changed. In order to adapt and gain access to the demands of the international market, particularly in Britain and Germany, he adopted the techniques of Francisco Domingo and Mariano Fortuny. Through small, precise brushstrokes like Fortuny's, his objects took on a sharply-defined, meticulous character, with the painter pausing to concentrate on the detail of different qualities and textures with a loose, rapid execution reminiscent of filigree – and always with dealers' tastes in mind. The finish characteristic of these pictures is not only the result of Benlliure's particular technique but, above all, of his extraordinary use of colour. In this respect, contemporary critics again compared him to his master Domingo.

This picture brings together two themes – markets and Valencian florists – regularly featured by Benlliure in his Rome period, and links up with oil paintings with often repetitive titles: Florista valenciana (“Valencian Florist”), Fioraia valenciana, Florista valenciana con traje típico del país (“Valencian Florist in Typical Regional Dress”), Mercado (“Market”), Mercado Árabe (“Arab Market”), Mercado de Tánger (“Tangiers Market”), Mercado de Tetuán (“Tétouan Market”), Tiendecilla de florist (“Florist's Stall”), Visita del cura a la florista de Aldaya (“Visit by the Priest to the Florist at Aldaya”), etc.

All the characteristics of technique and colour described as typical of Benlliure's artistic style during his stay in Rome can be observed in this painting, whose meticulousness and wealth of colour serve to emphasise the complexity of its thematic and idiomatic elements. It depicts a flower market supposedly on the Real de Valencia esplanade at the gates to the garden known as the Jardín de los Viveros. Although there is no actual historical record of the existence of a market of any kind in this part of Valencia, the perspective and the buildings on the skyline in the background are real. The Miguelete Tower, the dome of St Dominic's church, the tower of St Catherine's and the Serranos gates in this painting look just as they would have looked at that time when viewed from the Real Bridge. However, the fact that the sheen of the ceramic tiles on the dome of St Dominic's is gold rather than blue (as in the painting), confirms the supposition that the background was not actually taken from life but possibly from a photograph.

The main scene is situated beneath the branches of a number of plane trees which thus frame and delimit the right half of the composition. Both the woman selling her wares and the local man unloading flowers from a donkey harnessed as if for a feast day are dressed in typical Valencian costume. The two customers, however, wear Goya-style manola dresses like those popularised by Fortuny in The Spanish Wedding. The "stall" is actually a Classical stone balustrade draped at the front with an Eastern carpet and surrounded by flowers and green and black grapes inside an assortment of containers: Chinese vases, Moorish ceramic jars with metallic sheens, Renaissance garden pots, wicker and esparto-grass baskets. The group of figures on the left consists of girls and young women making small bouquets with discarded flowers. All are dressed in Roman peasant costume, like those depicted by the different "colonies" of foreign artists who worked in Rome. In the background are more flower stalls with groups of figures also in a variety of typical 18th-century working-class attire, as well as girls in 19th-century Valencian peasant costume and fine ladies in elegant 18th-century dresses.

The evident lack of historical realism in the subject matter and the peculiarities of the personages are offset by the absolute realism of the scene and unified by a conventional lighting with little contrast that endows the whole painting with a timeless quality. The painter's creative self-confidence, the visual sharpness of the composition and painstaking attention to detail – capable of standing up to analysis with a magnifying glass – all add authenticity to a scene which, although inherently false, has been described by many international collectors as “genuinely Spanish”.

Carmen Gracia